![The King climbing the chrystal tower to Zoulvisia, illustration from The Olive Fairy Book by Andrew Lang (1907)]()

The King climbing the chrystal tower to Zoulvisia, illustration from The Olive Fairy Book by Andrew Lang (1907)

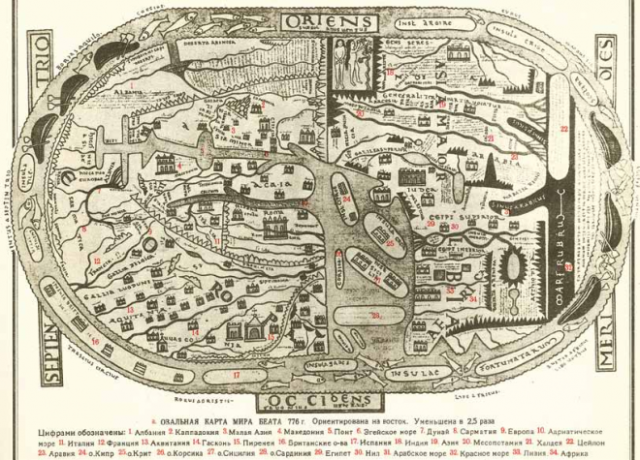

Folk tales are traditionally passed down generations through oral traditions and as such they tend to get lost in the mists of history. Some make it into books recorded by curious scholars, others completely forgotten. It is therefore always a delight to stumble upon tales recorded or otherwise translated by foreign travelers and scholars interested in Armenian folklore. One of such scholars was the French orientalist Frédéric Macler. Macler was a specialist in Oriental Languages and Civilizations, having learned Armenian, Assyrian and Hebrew. He is credited with hundreds of articles on Armenian language, history, architecture, music and miniatures. Among his achievements are his French translations of old Armenian legends and fairy tales. In his book “Contes Armeniens” (Armenian Tales, 1905) he has collected dozens of Armenian legends, folklore and fairy tales. One of these tales “The Story of Zoulvisia” was later translated into English by Andrew Lang and included in “The Olive Fairy Book” (1907). The story was also featured in the book Once Long Ago, by Roger Lancelyn Green.

By clicking the links you can read both of these books in their entirety. I’d love to read more from “Contes Armeniens”, unfortunately my French is fairly basic. But for those interested go ahead and explore more of these interesting tales. Furthermore by going HERE you can listen to the entire English version as an audiobook. Bellow follows Andrew Lang’s translation of The Story of Zoulvisia from “The Olive Fairy Book” (1907):

The Story of Zoulvisia

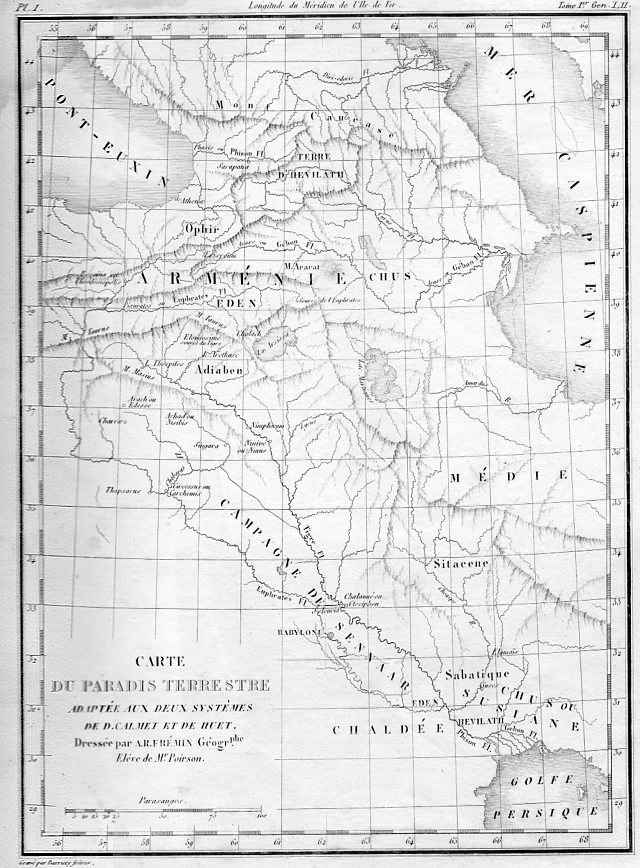

In the midst of a sandy desert, somewhere in Asia, the eyes of travellers are refreshed by the sight of a high mountain covered with beautiful trees, among which the glitter of foaming waterfalls may be seen in the sunlight. In that clear, still air it is even possible to hear the song of the birds, and smell of the flowers; but though the mountain is plainly inhabited—for here and there a white tent is visible—none of the kings or princes who pass it on the road to Babylon or Baalbec ever plunge into its forests—or, if they do, they never come back. Indeed, so great is the terror caused by the evil reputation of the mountain that fathers, on their death-beds, pray their sons never to try to fathom its mysteries. But in spite of its ill-fame, a certain number of young men every year announce their intention of visiting it and, as we have said, are never seen again.

Now there was once a powerful king who ruled over a country on the other side of the desert, and, when dying, gave the usual counsel to his seven sons. Hardly, however, was he dead than the eldest, who succeeded to the throne, announced his intention of hunting in the enchanted mountain. In vain the old men shook their heads and tried to persuade him to give up his mad scheme. All was useless; he went, but did not return; and in due time the throne was filled by his next brother.

And so it happened to the other five, but when the youngest became king, and he also proclaimed a hunt in the mountain, a loud lament was raised in the city.

‘Who will reign over us when you are dead? For dead you surely will be,’ cried they. ‘Stay with us, and we will make you happy.’ And for a while he listened to their prayers, and the land grew rich and prosperous under his rule. But in a few years the restless fit again took possession of him, and this time he would hear nothing. Hunt in that forest he would, and calling his friends and attendants round him, he set out one morning across the desert.

They were riding through a rocky valley, when a deer sprang up in front of them and bounded away. The king instantly gave chase, followed by his attendants; but the animal ran so swiftly that they never could get up to it, and at length it vanished in the depths of the forest.

Then the young man drew rein for the first time, and looked about him. He had left his companions far behind, and, glancing back, he beheld them entering some tents, dotted here and there amongst the trees. For himself, the fresh coolness of the woods was more attractive to him than any food, however delicious, and for hours he strolled about as his fancy led him.

By-and-by, however, it began to grow dark, and he thought that the moment had arrived for them to start for the palace. So, leaving the forest with a sigh, he made his way down to the tents, but what was his horror to find his men lying about, some dead, some dying. These were past speech, but speech was needless. It was as clear as day that the wine they had drunk contained deadly poison.

‘I am too late to help you, my poor friends,’ he said, gazing at them sadly; ‘but at least I can avenge you! Those that have set the snare will certainly return to see to its working. I will hide myself somewhere, and discover who they are!’

Near the spot where he stood he noticed a large walnut tree, and into this he climbed. Night soon fell, and nothing broke the stillness of the place; but with the earliest glimpse of dawn a noise of galloping hoofs was heard.

Pushing the branches aside the young man beheld a youth approaching, mounted on a white horse. On reaching the tents the cavalier dismounted, and closely inspected the dead bodies that lay about them. Then, one by one, he dragged them to a ravine close by and threw them into a lake at the bottom. While he was doing this, the servants who had followed him led away the horses of the ill-fated men, and the courtiers were ordered to let loose the deer, which was used as a decoy, and to see that the tables in the tents were covered as before with food and wine.

Having made these arrangements he strolled slowly through the forest, but great was his surprise to come upon a beautiful horse hidden in the depths of a thicket.

‘There was a horse for every dead man,’ he said to himself. ‘Then whose is this?’

‘Mine!’ answered a voice from a walnut tree close by. ‘Who are you that lure men into your power and then poison them? But you shall do so no longer. Return to your house, wherever it may be, and we will fight before it!’

The cavalier remained speechless with anger at these words; then with a great effort he replied:

‘I accept your challenge. Mount and follow me. I am Zoulvisia.’ And, springing on his horse, he was out of sight so quickly that the king had only time to notice that light seemed to flow from himself and his steed, and that the hair under his helmet was like liquid gold.

Clearly, the cavalier was a woman. But who could she be? Was she queen of all the queens? Or was she chief of a band of robbers? She was neither: only a beautiful maiden.

![Illustration from The Olive Fairy Book by Andrew Lang]()

Illustration from The Olive Fairy Book by Andrew Lang

Wrapped in these reflections, he remained standing beneath the walnut tree, long after horse and rider had vanished from sight. Then he awoke with a start, to remember that he must find the way to the house of his enemy, though where it was he had no notion. However, he took the path down which the rider had come, and walked along it for many hours till he came to three huts side by side, in each of which lived an old fairy and her sons.

The poor king was by this time so tired and hungry that he could hardly speak, but when he had drunk some milk, and rested a little, he was able to reply to the questions they eagerly put to him.

‘I am going to seek Zoulvisia,’ said he, ‘she has slain my brothers and many of my subjects, and I mean to avenge them.’

He had only spoken to the inhabitants of one house, but from all three came an answering murmur.

‘What a pity we did not know! Twice this day has she passed our door, and we might have kept her prisoner.’

But though their words were brave their hearts were not, for the mere thought of Zoulvisia made them tremble.

‘Forget Zoulvisia, and stay with us,’ they all said, holding out their hands; ‘you shall be our big brother, and we will be your little brothers.’ But the king would not.

Drawing from his pocket a pair of scissors, a razor and a mirror, he gave one to each of the old fairies, saying:

‘Though I may not give up my vengeance I accept your friendship, and therefore leave you these three tokens. If blood should appear on the face of either know that my life is in danger, and, in memory of our sworn brotherhood, come to my aid.’

‘We will come,’ they answered. And the king mounted his horse and set out along the road they showed him.

By the light of the moon he presently perceived a splendid palace, but, though he rode twice round it, he could find no door. He was considering what he should do next, when he heard the sound of loud snoring, which seemed to come from his feet. Looking down, he beheld an old man lying at the bottom of a deep pit, just outside the walls, with a lantern by his side.

‘Perhaps he may be able to give me some counsel,’ thought the king; and, with some difficulty, he scrambled into the pit and laid his hand on the shoulder of the sleeper.

‘Are you a bird or a snake that you can enter here?’ asked the old man, awakening with a start. But the king answered that he was a mere mortal, and that he sought Zoulvisia.

‘Zoulvisia? The world’s curse?’ replied he, gnashing his teeth. ‘Out of all the thousands she has slain I am the only one who has escaped, though why she spared me only to condemn me to this living death I cannot guess.’

‘Help me if you can,’ said the king. And he told the old man his story, to which he listened intently.

‘Take heed then to my counsel,’ answered the old man. ‘Know that every day at sunrise Zoulvisia dresses herself in her jacket of pearls, and mounts the steps of her crystal watch-tower. From there she can see all over her lands, and behold the entrance of either man or demon. If so much as one is detected she utters such fearful cries that those who hear her die of fright. But hide yourself in a cave that lies near the foot of the tower, and plant a forked stick in front of it; then, when she has uttered her third cry, go forth boldly, and look up at the tower. And go without fear, for you will have broken her power.’

Word for word the king did as the old man had bidden him, and when he stepped forth from the cave, their eyes met.

‘You have conquered me,’ said Zoulvisia, ‘and are worthy to be my husband, for you are the first man who has not died at the sound of my voice!’ And letting down her golden hair, she drew up the king to the summit of the tower as with a rope. Then she led him into the hall of audience, and presented him to her household.

‘Ask of me what you will, and I will grant it to you,’ whispered Zoulvisia with a smile, as they sat together on a mossy bank by the stream. And the king prayed her to set free the old man to whom he owed his life, and to send him back to his own country.

——————————————————-

‘I have finished with hunting, and with riding about my lands,’ said Zoulvisia, the day that they were married. ‘The care of providing for us all belongs henceforth to you.’ And turning to her attendants, she bade them bring the horse of fire before her.

‘This is your master, O my steed of flame,’ cried she; ‘and you will serve him as you have served me.’ And kissing him between his eyes, she placed the bridle in the hand of her husband.

The horse looked for a moment at the young man, and then bent his head, while the king patted his neck and smoothed his tail, till they felt themselves old friends. After this he mounted to do Zoulvisia’s bidding, but before he started she gave him a case of pearls containing one of her hairs, which he tucked into the breast of his coat.

He rode along for some time, without seeing any game to bring home for dinner. Suddenly a fine stag started up almost under his feet, and he at once gave chase. On they sped, but the stag twisted and turned so that the king had no chance of a shot till they reached a broad river, when the animal jumped in and swam across. The king fitted his cross-bow with a bolt, and took aim, but though he succeeded in wounding the stag, it contrived to gain the opposite bank, and in his excitement he never observed that the case of pearls had fallen into the water.

——————————————————-

The stream, though deep, was likewise rapid, and the box was swirled along miles, and miles, and miles, till it was washed up in quite another country. Here it was picked up by one of the water-carriers belonging to the palace, who showed it to the king. The workmanship of the case was so curious, and the pearls so rare, that the king could not make up his mind to part with it, but he gave the man a good price, and sent him away. Then, summoning his chamberlain, he bade him find out its history in three days, or lose his head.

But the answer to the riddle, which puzzled all the magicians and wise men, was given by an old woman, who came up to the palace and told the chamberlain that, for two handfuls of gold, she would reveal the mystery.

Of course the chamberlain gladly gave her what she asked, and in return she informed him that the case and the hair belonged to Zoulvisia.

‘Bring her hither, old crone, and you shall have gold enough to stand up in,’ said the chamberlain. And the old woman answered that she would try what she could do.

She went back to her hut in the middle of the forest, and standing in the doorway, whistled softly. Soon the dead leaves on the ground began to move and to rustle, and from underneath them there came a long train of serpents. They wriggled to the feet of the witch, who stooped down and patted their heads, and gave each one some milk in a red earthen basin. When they had all finished, she whistled again, and bade two or three coil themselves round her arms and neck, while she turned one into a cane and another into a whip. Then she took a stick, and on the river bank changed it into a raft, and seating herself comfortably, she pushed off into the centre of the stream.

All that day she floated, and all the next night, and towards sunset the following evening she found herself close to Zoulvisia’s garden, just at the moment that the king, on the horse of flame, was returning from hunting.

‘Who are you?’ he asked in surprise; for old women travelling on rafts were not common in that country. ‘Who are you, and why have you come here?’

‘I am a poor pilgrim, my son,’ answered she, ‘and having missed the caravan, I have wandered foodless for many days through the desert, till at length I reached the river. There I found this tiny raft, and to it I committed myself, not knowing if I should live or die. But since you have found me, give me, I pray you, bread to eat, and let me lie this night by the dog who guards your door!’

This piteous tale touched the heart of the young man, and he promised that he would bring her food, and that she should pass the night in his palace.

‘But mount behind me, good woman,’ cried he, ‘for you have walked far, and it is still a long way to the palace.’ And as he spoke he bent down to help her, but the horse swerved on one side.

And so it happened twice and thrice, and the old witch guessed the reason, though the king did not.

‘I fear to fall off,’ said she; ‘but as your kind heart pities my sorrows, ride slowly, and lame as I am, I think I can manage to keep up.’

At the door he bade the witch to rest herself, and he would fetch her all she needed. But Zoulvisia his wife grew pale when she heard whom he had brought, and besought him to feed the old woman and send her away, as she would cause mischief to befall them.

The king laughed at her fears, and answered lightly:

‘Why, one would think she was a witch to hear you talk! And even if she were, what harm could she do to us?’ And calling to the maidens he bade them carry her food, and to let her sleep in their chamber.

Now the old woman was very cunning, and kept the maidens awake half the night with all kinds of strange stories. Indeed, the next morning, while they were dressing their mistress, one of them suddenly broke into a laugh, in which the others joined her.

‘What is the matter with you?’ asked Zoulvisia. And the maid answered that she was thinking of a droll adventure told them the evening before by the new-comer.

‘And, oh, madam!’ cried the girl, ‘it may be that she is a witch, as they say; but I am sure she never would work a spell to harm a fly! And as for her tales, they would pass many a dull hour for you, when my lord was absent!’

So, in an evil hour, Zoulvisia consented that the crone should be brought to her, and from that moment the two were hardly ever apart.

——————————————————-

One day the witch began to talk about the young king, and to declare that in all the lands she had visited she had seen none like him.

‘It was so clever of him to guess your secret so as to win your heart,’ said she. ‘And of course he told you his, in return?’

‘No, I don’t think he has got any,’ returned Zoulvisia.

‘Not got any secrets?’ cried the old woman scornfully. ‘That is nonsense! Every man has a secret, which he always tells to the woman he loves. And if he has not told it to you, it is that he does not love you!’

![The Witch and her snakes, illustration from The Tale of Zoulvisia]()

The Witch and her snakes, illustration from The Tale of Zoulvisia

These words troubled Zoulvisia mightily, though she would not confess it to the witch. But the next time she found herself alone with her husband, she began to coax him to tell her in what lay the secret of his strength. For a long while he put her off with caresses, but when she would be no longer denied, he answered:

‘It is my sabre that gives me strength, and day and night it lies by my side. But now that I have told you, swear upon this ring, that I will give you in exchange for yours, that you will reveal it to nobody.’ And Zoulvisia swore; and instantly hastened to betray the great news to the old woman.

Four nights later, when all the world was asleep, the witch softly crept into the king’s chamber and took the sabre from his side as he lay sleeping. Then, opening her lattice, she flew on to the terrace and dropped the sword into the river.

The next morning everyone was surprised because the king did not, as usual, rise early and go off to hunt. The attendants listened at the keyhole and heard the sound of heavy breathing, but none dared enter, till Zoulvisia pushed past. And what a sight met their gaze! There lay the king almost dead, with foam on his mouth, and eyes that were already closed. They wept, and they cried to him, but no answer came.

Suddenly a shriek broke from those who stood hindmost, and in strode the witch, with serpents round her neck and arms and hair. At a sign from her they flung themselves with a hiss upon the maidens, whose flesh was pierced with their poisonous fangs. Then turning to Zoulvisia, she said:

‘I give you your choice—will you come with me, or shall the serpents slay you also?’ And as the terrified girl stared at her, unable to utter one word, she seized her by the arm and led her to the place where the raft was hidden among the rushes. When they were both on board she took the oars, and they floated down the stream till they had reached the neighbouring country, where Zoulvisia was sold for a sack of gold to the king.

Now, since the young man had entered the three huts on his way through the forest, not a morning had passed without the sons of the three fairies examining the scissors, the razor and the mirror, which the young king had left them. Hitherto the surfaces of all three things had been bright and undimmed, but on this particular morning, when they took them out as usual, drops of blood stood on the razor and the scissors, while the little mirror was clouded over.

‘Something terrible must have happened to our little brother,’ they whispered to each other, with awestruck faces; ‘we must hasten to his rescue ere it be too late.’ And putting on their magic slippers they started for the palace.

The servants greeted them eagerly, ready to pour forth all they knew, but that was not much; only that the sabre had vanished, none knew where. The new-comers passed the whole of the day in searching for it, but it could not be found, and when night closed in, they were very tired and hungry. But how were they to get food? The king had not hunted that day, and there was nothing for them to eat. The little men were in despair, when a ray of the moon suddenly lit up the river beneath the walls.

‘How stupid! Of course there are fish to catch,’ cried they; and running down to the bank they soon succeeded in landing some fine fish, which they cooked on the spot. Then they felt better, and began to look about them.

Further out, in the middle of the stream, there was a strange splashing, and by-and-by the body of a huge fish appeared, turning and twisting as if in pain. The eyes of all the brothers were fixed on the spot, when the fish leapt in the air, and a bright gleam flashed through the night. ‘The sabre!’ they shouted, and plunged into the stream, and with a sharp tug, pulled out the sword, while the fish lay on the water, exhausted by its struggles. Swimming back with the sabre to land, they carefully dried it in their coats, and then carried it to the palace and placed it on the king’s pillow. In an instant colour came back to the waxen face, and the hollow cheeks filled out. The king sat up, and opening his eyes he said:

‘Where is Zoulvisia?’

‘That is what we do not know,’ answered the little men; ‘but now that you are saved you will soon find out.’ And they told him what had happened since Zoulvisia had betrayed his secret to the witch.

‘Let me go to my horse,’ was all he said. But when he entered the stable he could have wept at the sight of his favourite steed, which was nearly in as sad a plight as his master had been. Languidly he turned his head as the door swung back on its hinges, but when he beheld the king he rose up, and rubbed his head against him.

‘Oh, my poor horse! How much cleverer were you than I! If I had acted like you I should never have lost Zoulvisia; but we will seek her together, you and I.’

——————————————————-

For a long while the king and his horse followed the course of the stream, but nowhere could he learn anything of Zoulvisia. At length, one evening, they both stopped to rest by a cottage not far from a great city, and as the king was lying outstretched on the grass, lazily watching his horse cropping the short turf, an old woman came out with a wooden bowl of fresh milk, which she offered him.

He drank it eagerly, for he was very thirsty, and then laying down the bowl, began to talk to the woman, who was delighted to have someone to listen to her conversation.

‘You are in luck to have passed this way just now,’ said she, ‘for in five days the king holds his wedding banquet. Ah! but the bride is unwilling, for all her blue eyes and her golden hair! And she keeps by her side a cup of poison, and declares that she will swallow it rather than become his wife. Yet he is a handsome man too, and a proper husband for her—more than she could have looked for, having come no one knows whither, and bought from a witch——’

The king started. Had he found her after all? His heart beat violently, as if it would choke him; but he gasped out:

‘Is her name Zoulvisia?’

‘Ay, so she says, though the old witch—— But what ails you?’ she broke off, as the young man sprang to his feet and seized her wrists.

‘Listen to me,’ he said. ‘Can you keep a secret?’

‘Ay,’ answered the old woman again, ‘if I am paid for it.’

‘Oh, you shall be paid, never fear—as much as your heart can desire! Here is a handful of gold: you shall have as much again if you will do my bidding.’ The old crone nodded her head.

‘Then go and buy a dress such as ladies wear at court, and manage to get admitted into the palace, and into the presence of Zoulvisia. When there, show her this ring, and after that she will tell you what to do.’

So the old woman set off, and clothed herself in a garment of yellow silk, and wrapped a veil closely round her head. In this dress she walked boldly up the palace steps behind some merchants whom the king had sent for to bring presents for Zoulvisia.

At first the bride would have nothing to say to any of them; but on perceiving the ring, she suddenly grew as meek as a lamb. And thanking the merchants for their trouble, she sent them away, and remained alone with her visitor.

‘Grandmother,’ asked Zoulvisia, as soon as the door was safely shut, ‘where is the owner of this ring?’

‘In my cottage,’ answered the old woman, ‘waiting for orders from you.’

‘Tell him to remain there for three days; and now go to the king of this country, and say that you have succeeded in bringing me to reason. Then he will let me alone and will cease to watch me. On the third day from this I shall be wandering about the garden near the river, and there your guest will find me. The rest concerns myself only.’

——————————————————-

The morning of the third day dawned, and with the first rays of the sun a bustle began in the palace; for that evening the king was to marry Zoulvisia. Tents were being erected of fine scarlet cloth, decked with wreaths of sweet-smelling white flowers, and in them the banquet was spread. When all was ready a procession was formed to fetch the bride, who had been wandering in the palace gardens since daylight, and crowds lined the way to see her pass. A glimpse of her dress of golden gauze might be caught, as she passed from one flowery thicket to another; then suddenly the multitude swayed, and shrank back, as a thunderbolt seemed to flash out of the sky to the place where Zoulvisia was standing. Ah! but it was no thunderbolt, only the horse of fire! And when the people looked again, it was bounding away with two persons on its back.

——————————————————-

Zoulvisia and her husband both learnt how to keep happiness when they had got it; and that is a lesson that many men and woman never learn at all. And besides, it is a lesson which nobody can teach, and that every boy and girl must learn for themselves.

(From Contes Arméniens. Par Frédéric Macler.)

__________________________________________________________________________

![]()

![]()